Jehanabad: Of Love and War- A Specter Is Haunting Jehanabad

One put love as a theme in their film, one might have taken a substantial risk to not show the same repetition. The repetition, which you see always and want to see one more time.

If Marx were born in Jehanabad, he might have written: "A specter is haunting Jehanabad—the specter of Deepak Bhaiya."

If Mao had gotten the opportunity to see the specter of Deepak Bhaiya, he might have said, "Power flows through the edges of the blade."

The specter of Deepak Bhaiya first haunts you with his poignant face, calms you with his ordinary life, and then convinces you with his eloquence in reciting rhetoric. His main task is to enlighten you—violence could be an answer.

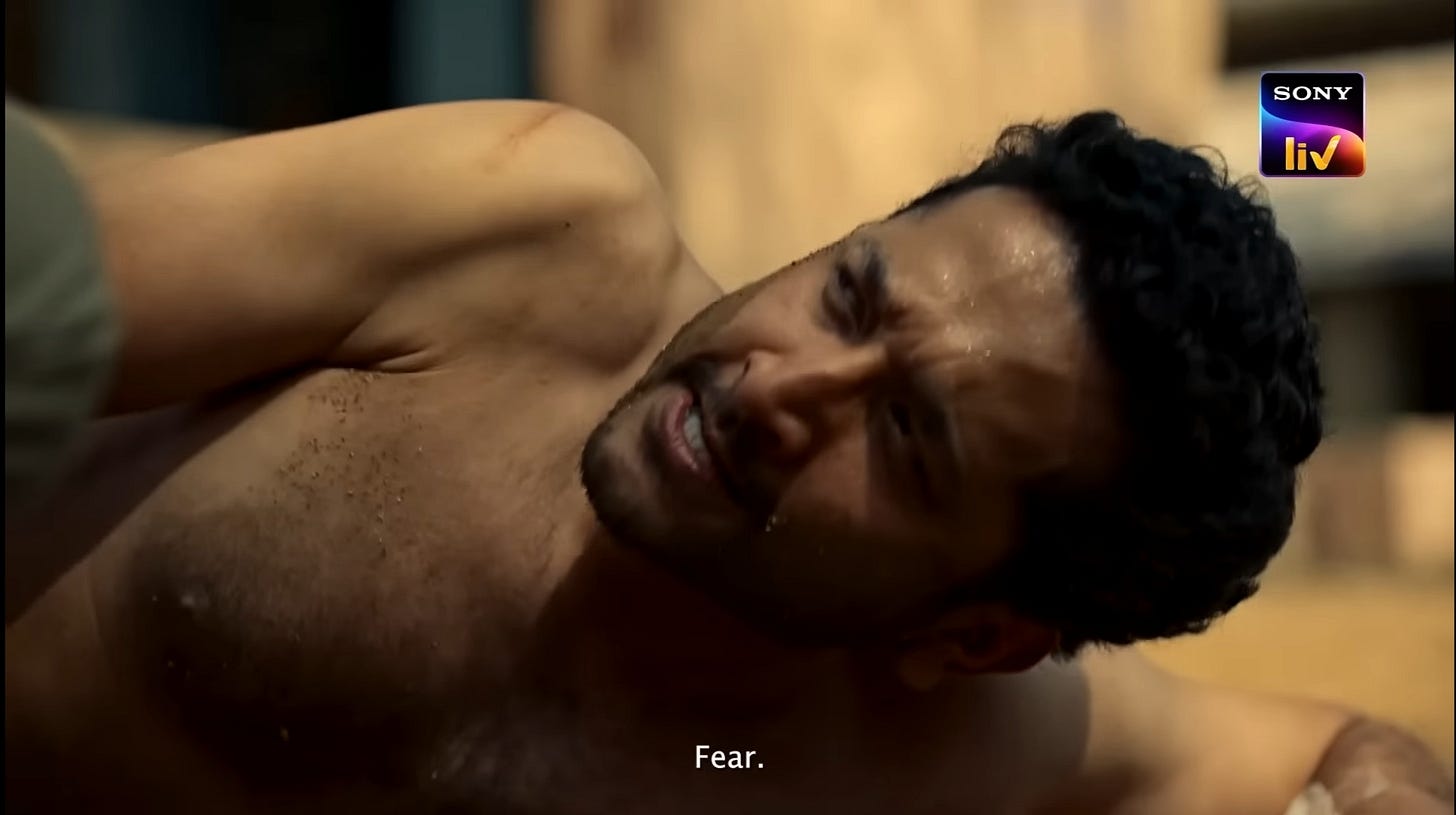

The unmitigated violence which he perpetuates through any object could make you click on your screen—you would feel it’s really a specter not a human. He would make you believe in this theory. "When you desire something badly enough, the entire universe conspires to give it." He follows it sincerely.

One would guess the unflinching specter of Deepak Bhaiya when the jailor pulls his face and utters, "Khana, Peena, Hagna, Mootna Jaam ho gaya hai, jab se Deepak Kumar aaya hai." (In short, as Deepak Bhaiya came to jail, the daily rituals of the jailor got jammed.) metaphorically and literally both.

The tightness in Deepak Bhaiya’s eyes overjoys you and demands a sincere amount of time to wonder over this persona—the persona of a Naxal commander.

Romantic love is another specter in the series that will haunt you. One put love as a theme in their film, one might have taken a substantial risk to not show the same repetition. The repetition, which you see always and want to see one more time.

It's the year 2005 in Jehanabad when Kasturi Mishra—a cheeky, erotically possessed literature student—dreamt of a sharp, tall, well-spoken, handsome husband for her. This dream, as it seems, could not be dreamt by a simple girl even in a town in 2005. It’s not even possible now. But Kasturi Mishra is not just a simple girl; she is a tool to show something vague, something dodgy.

This phenomenon of dreaming might be seen as a revolution. The revolution of small-town feminism. And when the stoic-lecturer, Abhimanyu Singh, appears: the emptiness of Kasturi gets filled in with his persona. The persona that is manipulative yet lovable. And Kasturi falls for the lovable part, as we all desire to fall for the lovable one.

You would make yourself aware at that moment of the juxtaposition, the sequential cut in scenes. The Naxal commander's arrest and the appearance of Abhimanyu Singh—explaining the love and revolution of Neruda— show you that something is being cooked there, which should be devoured.

I was fascinated with the character of Shibu Babu, an ex-MLA, who repeatedly told his guest while asking for food, "Ghar ke Gaay Ke Doodh Ka Bana Hai." While it could be taken just as a statement, I'd advise you not.

Milk, especially that of domesticated bovines, is treated with respect, and those who own it for them it is a symbol of power and property in rural areas. Even in rural areas, marriage could be fixed by just knowing how much land you acquire and how many bovines you are domesticating?

So Shibu Babu wants to be authoritative once again. But somehow he had doubts, and to clear that up, he always told everyone to look if I would get lost this time I have my own cattle—another powerful tool to show off.

Of all the episodes you see in Jehanabad: Of Love and War, which are gripping yet predictable, exciting yet boring, doubtful yet familiar, and amidst these when you are making yourself comfortable with sheer and sudden violence, a short episode might slip away from your eyes.

In that very scene, a character (the lecturer) introduces himself to a police officer: "Hum angreji padhate hain." And he, the police officer, with a cigarette in between his lips, replies calmly: "OK. Great. Very Good." Afterwards, he speaks Bihari-accented Hindi.

This typical bihari-bashing of English could stimulate a charming smile on your face. And I promise you that whenever you remember that scene, you will get a broad smile on your face.

In Bihar, you might get admiration for your good English, but people will never lose sight of the opportunity to make fun of you.

Last week I wrote for Outlook on Qala. You can read here.